“There is no such thing as a failed experiment, only experiments with unexpected outcomes”. Fear of failure inhibits change, yet understanding what produces it can lead to innovation. We look at the work of creators such as Buckminster Fuller, and how they experienced fear and uncertainty, but persist to innovate.

Going to zero

When someone asks, “what could possibly go wrong?” you know that something horrible is about to happen. It could be anything from mild embarrassment to a complete meltdown. Author and entrepreneur Jonathan Fields identifies the latter kind of experience as “going to zero”, and the fear of ‘zero’, or fear of failure, as one of the greatest that we experience today – particularly in our working lives.

Fields says fear of failure is an unholy trinity, made up of a fear of being judged by others, low tolerance for uncertainty, and anxiety about material losses. “Many of the world’s greatest creators, from traditional artists to entrepreneurs and global business builders, have gone to zero,” says Fields, but the experience “releases within them the freedom to rebuild.” Citing Harry Potter author J.K. Rowling’s resilience when she was penniless and without a publisher, Fields stresses that once you’ve experienced total ‘zero’ and realised that – to coin a phrase – it’s not the end of the world, the triple fear can melt away.

Author and entrepreneur Jonathan Fields identifies the latter kind of experience as “going to zero”, and the fear of ‘zero’, or fear of failure, as one of the greatest that we experience today – particularly in our working lives.

Inspiring as these, and similar examples, can be, it turns out that there is a solid basis for our antipathy towards zero point. Simply put, it represents a major threat, and our brains have evolved over millions of years to keep us out of harm’s way by avoiding threat. Change management expert Hilary Scarlett has spent the past few years working with leading neuroscientists at University College London to understand the impact of the brain’s structure and processes on modern organisational life.

While the brain is set up to both get us away from danger and seek pleasure, says Scarlett, “the threat response in our brains is far stronger than the reward response.” So, it’s not surprising that fear of failure remains such a common inhibitor of innovation, given the risks that go with it. The thing is, we’re not roaming the savannah any more, dodging snakes and tigers (well, not usually…). There are ways we can acknowledge and overcome the elements in going to zero’s three-way threat of judgment, uncertainty, and loss.

Bucky to the future

Designer, author, and inventor R. Buckminster (‘Bucky’) Fuller is a celebrated figure in design history. Creator of the iconic Geodesic Dome and Dymaxion map, his influence is still felt in areas from design and manufacturing to project management. But he was no stranger to failure.

Despite having already published and lectured widely after his military service in World War I, in 1927 Fuller found himself in Chicago with no job and no money. He was particularly disappointed by the failure of a construction company he’d set up to exploit the modular building methods he had developed. He felt betrayed by people around him, and was haunted by the loss of a daughter to polio five years earlier.

Seeing no future for himself, according to Fuller’s carefully-crafted self-history, he set off to throw himself into Lake Michigan. Just at the crucial moment a voice called out to him, telling him to return home, become vegetarian, and find a new purpose in life. This version of events is highly questionable, but the point is that although he had reached a nadir in his life, he learned there was always a way back. Fuller’s “unrelenting perseverance in the face of skepticism and outright rejection”, as the LA Review of Books describes it, became a central part of his universalist, future-oriented credo.

However, there’s no denying his influence, or the success of his best-known designs. But his very single-mindedness blinded him to other perspectives, and made some suspicious of his ideas. His perseverance got him through many obstacles partly because, at the time, very few other people understood the concepts he was advocating, such as “comprehensive anticipatory design science”.

With the benefit of hindsight, and developments in design thinking in the years since Fuller died, we are in a more fortunate position. We can grasp the significance of anticipatory design science, but we can do so in a more open and flexible way than Fuller himself was able to, and there are now tried-and-tested ways to liberate personal and organisational innovation from the fear of failure.

Space: The final frontier

One of the first steps any organisation or team can take is to allow its people to not know all the answers. In a recent article on this site, Joe Ferry showed how a business can help employees overcome their reluctance to say “I don’t know…” through a combination of leadership, brand, and belief. Ferry’s team at Virgin Atlantic harnessed their passion for the brand’s pioneering spirit to their empathy for the airline’s customers to provide “a starting point for innovation [that] is as good as it gets”.

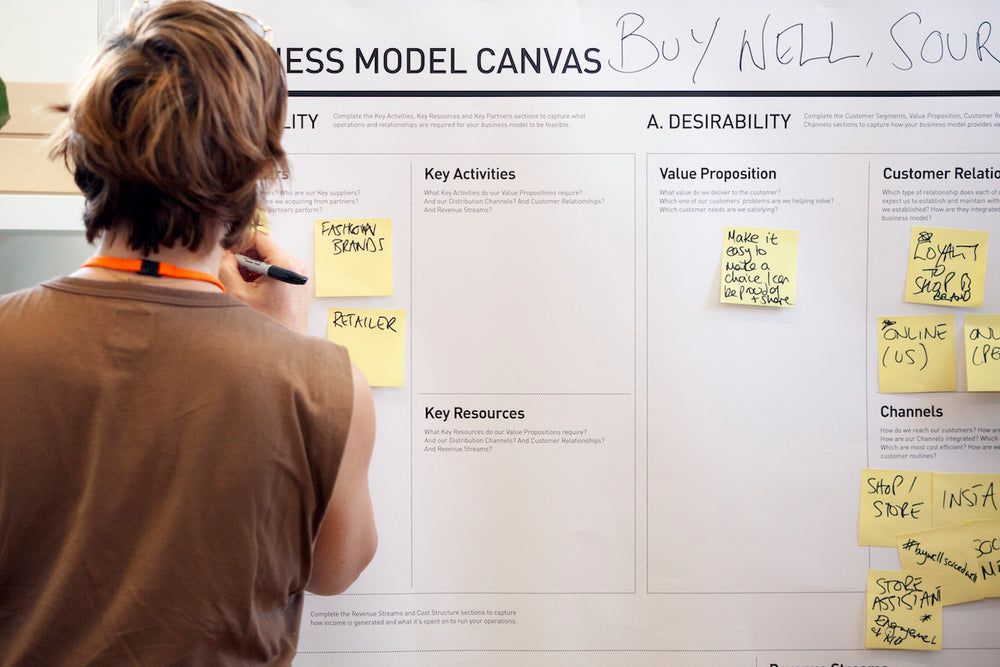

The collaborative, human-centred problem solving Virgin Atlantic adopted can provide the means to escape the tiger that scares us away from trying something new or different. To be capable of innovation, an organisation must adopt agile responses to emerging technologies, changing stakeholder demands, and unpredictable factors in the wider environment. Design methods and principles can promote such agile responses, and encourage a proactive stance towards new opportunities.

"To be capable of innovation, an organisation must adopt agile responses to emerging technologies, changing stakeholder demands, and unpredictable factors in the wider environment."

This involves promoting the idea that there is space within your organisation for innovation. In other words, your people need a sense of permission to do the things necessary for innovation to flourish. In their study, Spaces for Innovation: The Design and Science of Inspiring Environments, Kursty Groves and Oliver Marlow highlight five related spatial dimensions:

- Cognitive space, which is composed of individuals’ competences and skills

- Social space, or the networks of relationships among individuals within an organisation

- Organisational space, deriving from the relations between different groups or departments

- Institutional space among all the rules, routines, and structures that every organisation has

- Geographical space, or the physical distance between people and things

The digital environment is a sixth dimension, cutting across and connecting the others. Linked to space is the notion of proximity, which in this context refers to the closeness of an individual, group, or organisation to a particular project or task. Each organisation’s unique proximity matrix can be created by mapping teams and tasks across the six dimensions, providing a guide to where and how innovation can best be enabled.

Today’s business world is opening up more and more to ideas and methods from other sectors. Amy Whitaker, a practicing artist, writer, and teacher who holds Master’s degrees in both Fine Art and Business Administration, observes that “permission to try and fail frees you to ask questions that really matter.” Asking those questions can be risky, she admits in her new book Art Thinking, but that’s the beauty of it; “Only by changing our relationship to judgment and process can we open up that space of possibility”.

That requires us to try things out as we seek answers to those important questions. Without trial and error, without being willing to ‘just do it’ and see what happens, we will only ever have, at best, partial answers. As Bucky Fuller’s friend and collaborator Victor Papanek wrote, “the history of progress is littered with experimental failures”. Being willing to see what works and what doesn’t – and to learn from both – equates in business terms to more opportunities and more sustainable growth. Because even with the best plans and strategies, we can’t be certain how things will turn out. As Bucky himself put it, “How often I found where I should be going only by setting out for somewhere else.”